Grand Design, Unfinished

Lantenay bears the mark of a château imagined on a monumental scale - a grand design begun, yet left unfinished, perhaps as a sign of good judgment. For even without its planned quadrilateral and great logis, the family succeeded in giving the estate features of breathtaking audacity, above all the staircases that still astonish today.

To understand this balance of vision and restraint, we must turn to the family behind it - the Bouhier, whose intellect, faith, and means shaped both the dream and its limits.

The Bouhier Legacy - The forces that made Lantenay possible.

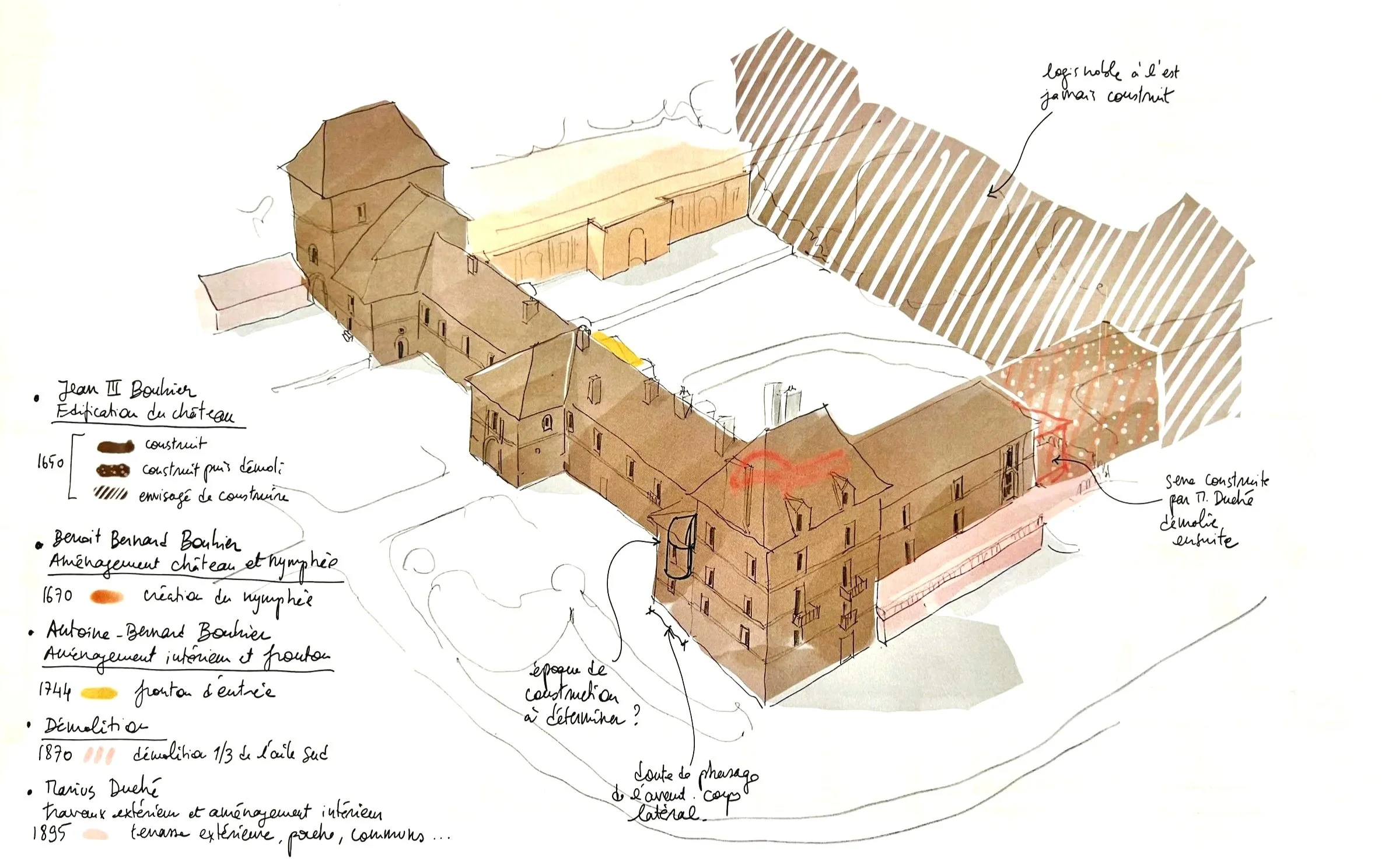

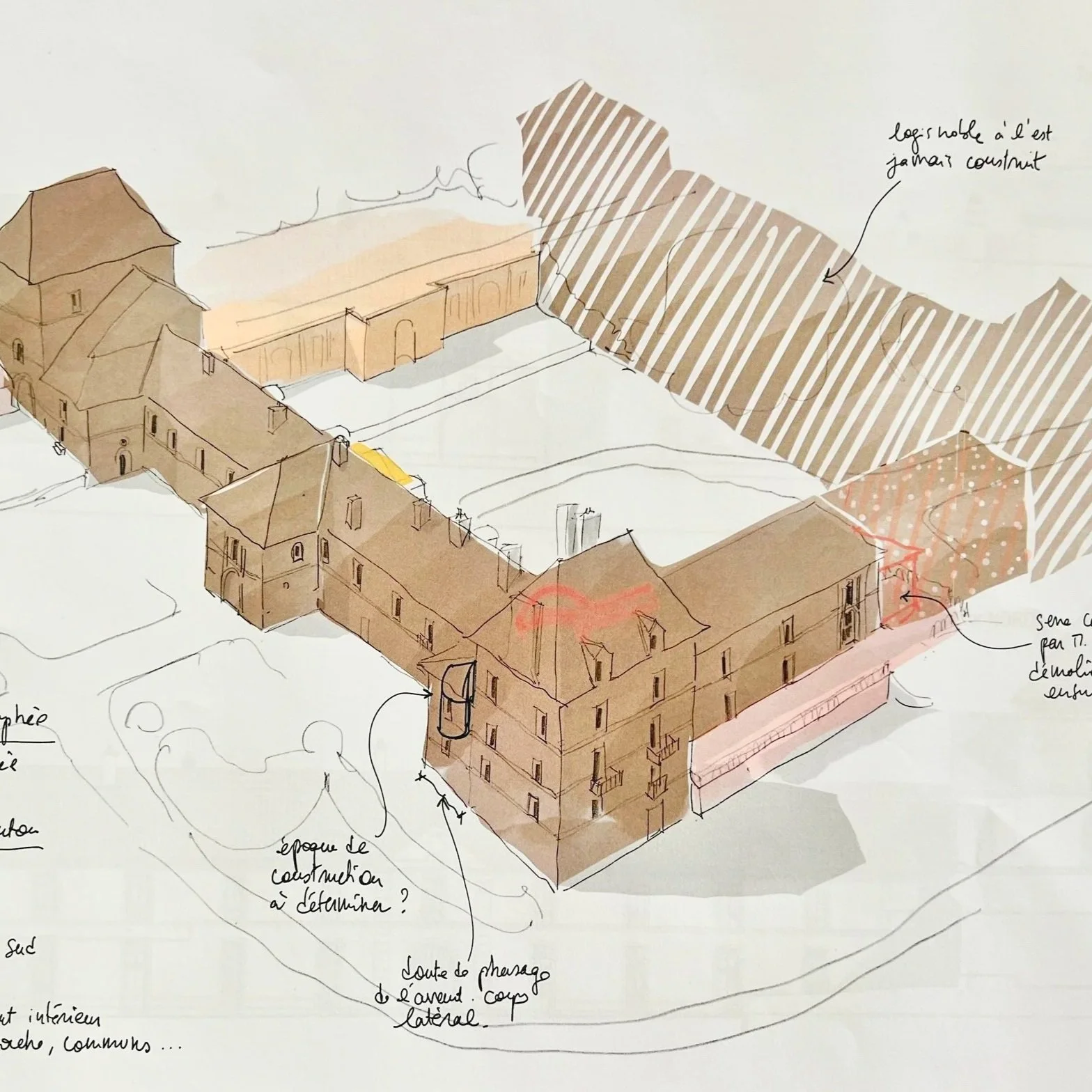

From 1619 to 1670, the illustrious Bouhier family erected the present-day château on the lands of the former medieval ducal domain, elevating it to the Marquisat de Beaumanoir, later known as the Marquisat Bouhier de Lantenay.

From the 16th to the 18th century, the Bouhier family gave Burgundy five présidents à mortier and numerous others as magistrates and conseillers in the Parlement de Bourgogne, the first and the second bishops of Dijon, an academician, and generations of patrons of architecture and the arts.

They left libraries of tens of thousands of volumes, founded hospitals, and were immortalized by painters such as Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Their presence helped shape Dijon in its law, its faith, its knowledge, and its culture over three centuries.

CGArt architectes

Yet behind the remarkable scale of the dynasty, it is their very human rhythm of priorities that proves most endearing.

The Bouhier purchased lands in Lantenay in 1619… and then? In spite of their immense means, the château itself only rose decades later, after three generations.

Why?

Because in the meantime, they poured their energy and resources into other priorities, such as the Hôpitaux Généraux in Dijon, where Étienne Bouhier and his circle played decisive financial roles.

Thus, their ambition expressed itself as a balance between public good (care, hospitals, service to the city) and private legacy (their estates, their monuments).

The delay gives Lantenay a curious charm: when at last the château rose in the 1650s, it felt less like ostentation and more like the inevitable flowering of a family that had already proven its stature..

In short: their greatness impresses, but their priorities endear them. Lantenay thus stands as the legacy of a lineage whose intellect, faith, and means made it possible.

The Bouhier Legacy at Lantenay

Jean II Bouhier (1546-1620) - The AcquirerPrésident à mortier of the Parlement de Bourgogne, Jean II acquired the seigneurie of Lantenay in 1619, laying the family’s foundation here. His tenure marked the first ambition to transform the medieval site into a residence reflecting the rising stature of Dijon’s legal and parliamentary elite.

Étienne Bouhier (1580-1635) - The VisionarySon of Jean II, Étienne inherited his father’s office as président à mortier. Educated in Padua, he brought back from Italy a cultivated taste for classical forms and urban magnificence. In Dijon he commissioned the Hôtel de Vogüé (1614–1617), still one of the city’s architectural jewels. He appears also to have conceived the grand projet of Lantenay - a quadrilateral château with axial gardens and monumental design - though his early death delayed its realization. His legacy blends civic works, architectural patronage, and the vision that his son Jean III would attempt to fulfill at Lantenay.

Jean III Bouhier (1607-1671) - The Constructor« Je l’ai faite de telle sorte que les ignorants n’y comprissent rien. »

“I made it in such a way that the ignorant would understand nothing of it.”

Paris: Fédéric Morel, 1567–1568), Livre VI, fols. 124v–125r.

-Philibert de l’Orme, describing the stereotomic geometry of his ‘escalier suspendu’ for the Tuileries.

The passage appears in his Premier tome de l’architecture (Paris, 1567–1568), around folios 124v–125r (Livre VI), where he sets out his stereotomic works for the Tuileries stair.

De l’Orme, Philibert. Premier tome de l’architecture. Paris: Fédéric Morel, 1567–1568.

At just 22, Jean III inherited Lantenay on his father’s death, along with the weight of an unfinished grand projet. From the 1640s he oversaw the construction of the château, including its most striking features: the staircases of the North and South towers. The virtuosity of these works - unmatched elsewhere in the region and absent from all Bouhier writings - begs the question: how did this young magistrate, without formal architectural training, achieve such masterpieces?

Philibert de l’Orme had famously left his helicoidal vaults as a kind of intellectual puzzle, his stereotomic methods obscured and not systematically explained until the 18th century. That they appear at Lantenay in the mid-17th century seems virtually a technical impossibility for their time and place. Whether Jean III relied on inherited plans, architectural treatises, the genius of local maîtres tailleurs de pierre, or still other enigmatic possibilities, his tenure gave the château the audacious features that continue to astonish both scholars and visitors alike.

Benoît-Bernard Bouhier (1642-1682) and Jeanne-Claude-Marie Gagne de Perrigny (1648-1724)The son of Jean III, Benoît-Bernard Bouhier became président au Grand Conseil and, in 1677, saw Lantenay and Pasques erected into a marquisat in his favor. Educated and worldly, he undertook a grand tour of Italy in 1664, cultivating a taste for classical gardens and architecture. During his short tenure as marquis, he is believed to have initiated embellishments at Lantenay, including the nymphæum with its terrace wall, glacière, and garden pavilion - today protected under the Monuments Historiques decree of 5 August 1988. These works introduced an Italianate accent that would be formalized in the following century.

His wife, Jeanne-Claude-Marie Gagne de Perrigny, added grace and presence to the lineage. Preserved in a beautiful portrait, she embodied the elegance and refinement of her time. Together they transmitted to their son Antoine-Bernard not only a title but also the ambition and cultural sensibility that would define the next chapter of Lantenay’s history.

Antoine-Bernard Bouhier (1672–1746) - The Magistrate of PrestigeHyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait d'Antoine-Bernard Bouhier, vers 1713, huile sur toile. Inv. CA 358. Saisie révolutionnaire, collection Bénigne Bouhier à Pouilly, 1793. © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/François Jay

Marquis de Lantenay and président à mortier of the Parlement de Bourgogne, Antoine-Bernard presided over the family’s final flowering here. His portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1713) placed him among Europe’s great dignitaries, yet at Lantenay he revealed a pragmatic side. Rather than pursuing the unfinished quadrilateral “grand design” conceived by his forebears, he chose to consolidate the existing château - ennobling its service wings into noble apartments, and crowning the façade with a heraldic fronton that unusually displayed the coats of arms of female family members. With this gesture he affirmed the château as complete in itself, no longer a basse-cour awaiting extension.

His voice also survives: in letters preserved and later published by Félix Chary (1923–24), Antoine-Bernard emerges as a man of wit and refinement - and above all as one who deeply loved Lantenay. His affection for the estate transpires in every line, marking him as the Bouhier who left not only works of stone, but also words of attachment. Without a direct heir, he bequeathed Lantenay to his nephew, thus closing the Bouhier line at the château. His tenure left both the most vivid personal trace of any Bouhier, and the definitive form of the monument we see today.